A Walk on Bodmin Moor

Sandra Pritchard

No one who walks upon the high moorland of Cornwall can fail to have their soul stirred by its silence and lonely grandeur. The upland hills of Bodmin Moor are no exception. Here they smell of peaty bog, heather and ling. Small stands of gorse give off the faint aroma of marzipan and the silence is so great that you can almost believe you have gone deaf.

The high plateaus have no flower be-decked water meadows, nor are there any stately trees to cast their shade. Its beauty has a more ethereal quality, an other-worldliness, it’s treasures often hidden from view by a diaphanous veil of mist. When the fog comes down, the unwary traveller can sometimes experience a rip in the curtain of time. The unseen tempts the walker ever onward into its very heart. The grey surfaces of the many boulders strewn about are dappled with the yellow-ochre of lichens. At one time you would have seen turf stacked up in rows that marched of into the distance. Peat was cut as a valuable fuel source, in fact the only one in this treeless land. Dotted about the landscape are the many pools and ditches left by the peat men. Their still inky blackness is strangely forbidding and now and then a bubble of methane gas escapes from their depths to the surface, bursting with a plop!

Peat cutters near Brown Willy,

These moorland men would cut into the turf with their special shovels and place the perfect oblongs into piles some 2-3 foot high as they went. They were left to drain over the course of the summer. Before the autumn rains worked their worst they would be back, to load the now shrunken turves onto horse-drawn carts. They would haul them away to the nearest stone road, there to be stored in high stacks until needed during the bleak winter days. Access to the open moor with a wheeled vehicle was impossible during the winter months. The low lying wet ground quickly turned to mire and bog, ready to trap the unwary. The added hazard of the frequent mists and freezing fog would dissuade any but the most foolhardy from traveling this way without good reason.

Roughtor: packhorse bridge.

This of course was a good time for the pack mules of the 'gentlemen' bringing their trade goods to the isolated homes and inns of the high moors. Strangers were unlikely to be abroad and the locals knew well when to keep themselves scarce.

The peat cutters pools are rain-catchers as the underlying geology of the ground is formed from kaolin, more commonly known as china clay. This acts as a seal and water is unable to drain away freely. The puddles and ponds are topped up with each successive rainfall- which are often frequent and heavy- until the body of water is quite large. Springs do not drain into them. They are more free flowing spirits and they soon escape from the bog-ridden landscape to the delights of the more sylvan valleys below.

A climb to the summit of either Brown Willy or Roughtor [Rowter] will reveal the silvery threads of the many infant streams that are born on these slopes. They will pursue their course seaward, to the south or north, growing ever stronger, wider and more boisterous until they eventually tumble into the waiting arms of the sea.

View from Brown Willy westward.

Whilst on the heights, if we turn and cast our eyes westward we will see in the far distance the high tors of Penwith; the sea-guarded sanctuary of the old pagan beliefs, where winter dares not come and the camellias often blossom at Christmas time.

The moor here high on the Tor holds no such subtle charms, its beauty is laid bare in a more stark, naked form. The wind seems always to be on the move and the rain flies sideways, like demented demons with a sting in their tails. Here flowers cling close to Mother Earth for shelter from the ever-present storms. You will have to bend the knee low to see her gifts of potentilla, white bedstraw and whortleberry.

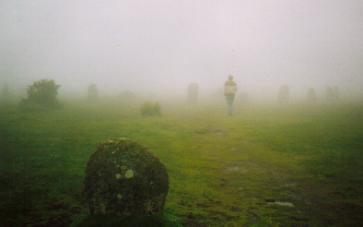

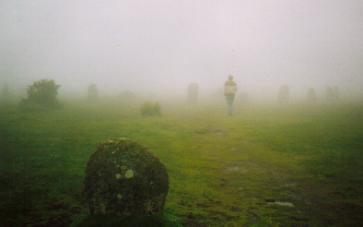

Stone Circle Bodmin Moor.

As you descend the eastern side of Brown Willy, near the base you will see a collection of beehive huts almost intact and, close by, another stone circle. Ancient man once lived, breathed and died within this, now harsh, environment. Perhaps this place was then a kinder and more gentle one than now. Who knows what climatic catastrophe overcame these settlements and caused them to gradually leave their upland homes. History leaves us no written record, save what can be deduced from clues hidden within the landscape itself..

Summit of Catshole Tor.

In front of us lies Catshole Tor

and below its summit, stretched across a flat plain, lies an ancient long barrow made of stones; the burial

place of some long forgotten tribal elder perhaps.

Catshole Long Downs Cairn

The original structure was originally of a roughly triangular shape, perhaps some 17 to 30 m long. All that remains is the large upright flat stone, which may have marked the entrance and also a few prostrate ones what might have been the flanking stones. This man-made structure is from the fourth millennia BC. Scattered far and wide around are many stones, perhaps once the building blocks of house and hearth and home; the last relics of what was once a fairly densely populated upland settlement.

Staying on the ancient track-way from Catshole Tor and over Blackadon we come eventually, after a three mile walk, to the now abandoned parish church of Holy Trinity at Bolventor (Bolven Tor).

The parish was created on 24th June 1848 from parts of Altarnun, St Neot and Cardinham parishes. The structure is of granite and stone in the Gothic style, comprising a chancel, nave and bell turret containing one bell. Sadly, it went out of use by the close of the 20th century.

A modern by-pass now cuts through what was once the footpath from the church to Bolventor village and its inn. In the mid 18th century a turnpike road, from Launceston to Bodmin, was constructed to take coaching traffic. It ran past the front door of what was then a little farmhouse kiddly-wink, an insignificant little building which developed into a grand and more commodious establishment entirely. There were stables for the change of horses, rooms for refreshment and accommodation for any weary traveller who wished to take their rest, after the perils of driving over the moor. It was known at first as the "New Inn" but the title 'New' was soon replaced with the soubriquet of "Jamaica".

This name was said to have been in recognition of the wealth of the owner of the New Inn, a local landowner whose fortune came from the many plantations he owned in that place. However, I prefer to think it was also a tribute to the finest of spirits originating from those sugar islands- and freely available within the new hostelries portals. Rum and shrub was a favourite with seafaring men, combining two of the kings of the spirit world, rum and brandy, as well as other ingredients all completely of foreign origin. [See Recipe Page]

This ancient watering hole is situated at the very centre of the moor, 1000 feet above sea level, and has become one of the best-known hostelries in the country, thanks to novelist Daphne du Maurier. Whilst staying there in the 1920s, she was not only taken with the romance of the surrounding bleak moorland but also fascinated by the tales of smugglers and other rogues who made the inn their meeting place.

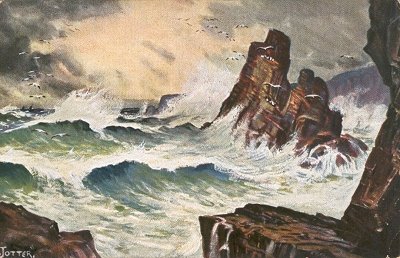

A less traveled ‘green road’ led to the ports, either of the south or the north coast. This was the chosen route of the ' free traders' as they brought their goods from their secret landing places on the shore, up to the villages of the high moorland parishes. If the weather were bad, or the coastguards too active along the Channel coasts, they would risk a journey around the Land’s End to land their valuable, custom free, cargo on one of the more inhospitable northern beaches. These had been well used at the time of the cattle-dealing and horse-trading with the Irish in the 16th century but any ship attempting to land on this fearful coast had to be in the hands of a skilled and fearless navigator. They could easily “come to grief” on the cruel rocks that lie scattered all about the base of the high granite cliffs.

Ghostly characters seem to come to the fore in the folklore of "Jamaica Inn" from around the date of the publication of Daphne du Maurier’s book in 1936 but there are also a couple of strange phenomenon with no apparent connection.

A sailor slipped out of the inn to meet up with someone, leaving behind his unfinished drink. He is said to have been last seen sitting on a low wall outside in the courtyard. The story goes, with no evidence of the event, that he was later found with his throat cut in a nearby field. His ghostly form still returns to the yard area but never back into the bar where his unfinished pint of ale awaits! Another, more modern manifestation, was seen by at least two independent witnesses on two separate occasions in the 1970’s. An old fashioned green car, containing four men who appeared to be laughing, vanishes almost as soon as it is seen, traveling along the old road towards Bodmin.

Before we enter the inn and enjoy its warmth and hospitality let us take a last short walk before sunset to view a site associated with " our once and future king"

Dozmary Pool: said to mean “a drop of sea”.

Dozmary Pool was once thought to be bottomless and to have a tunnel connecting it to the sea. It dried up in the year 1869 and was found to be extremely shallow with no tunnel exit evident, quashing any notions of truth in either legend. It is still oft repeated, despite another drought in the 1970's revealing no mysterious depths. Some exploration of the mud revealed Neolithic arrowheads in the dried up bed.

The place still holds a haunting beauty, however, and is best viewed at summer sunset. Its situation is remarkable; 1000 feet above the sea on a ridge with a deep valley to either side. No streams run into it and all around lays the wide silent moor, its horizons broken now and then by huge granite bosses or the monoliths and stone circles of prehistoric times.

As the gloaming gathers over the shoulders of the hills and the cloak of night descends in velvet softness, the last warm blush of the sun is reflected on the still bosom of the lake. Truly this place is touched by magic and as night falls

“

The arm clothed in White Samite, Mystic, Wonderful ”

could

so easily rise up gently from the

waters to firmly grasp the sword, Excalibur.

As the mantle of dusk blots out the landscape entirely white stars glitter overhead and

we fancy we can almost

“To

the island valley of Avalon

Where

falls not hail or rain or snow,

Nor

ever wind blows loudly, but it lies

Deep

meadow'd, happy, fair with orchard lawns

And bowery hollows crowned with summer seas”

We must return to the inn but as we look east, across to quarry country, you can imagine the past with men slaving away, hacking out a meager existence from the ground. Faint trails and remnants of dismantled railways criss-cross the area, from pit to pit and away to the surrounding villages.

They have gone, never to return but when the wind moans across Twelve Men's Moor it is said to be the sound of spirits walking.