The Tide Rises, The Tide Falls

by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

The tide rises, the tide falls,

The twilight darkens, the curlew calls;

Along the sea-sands damp and brown

The traveller hastens toward the town

And the tide rises, the tide falls.

Darkness settles on the roofs and walls

But the sea, the sea in darkness calls;

The little waves, with their soft, white hands,

Efface the footprints in the sands

And the tide rises, the tide falls.

The morning breaks; the steeds in their stalls

Stamp and neigh, as the hostler calls;

The day returns, but nevermore

Returns the traveller to the shore,

And the tide rises, the tide falls.

In

May 2003 Janet from Australia and a native of St Ives sent an e mail to

the list with a query. I replied at the time with some answers. I have since

tidied up the piece and give it here, together with Janet’s original

e mail

“Around about 1946/48 I was taking a walk with my grandparents, Mr & Mrs Hodge, after church, out Clodgy way. From the point we could see a man standing on a rock a good way from shore waving his arms and obviously in distress. The tide was coming in and waves were breaking over the rock. Someone must have gone for help as two boats came on the scene, but because of the swirling current around the rock the boat could not get to the man. My grandfather was signaling to the boat men with arm movements [sos?] This drama went on for a good while but when the waves got so strong that the man could hardly stand anymore, he made a dive across the swirl. He was a very lucky man to clear the whirlpool.I think this rock was names "Gowna Rock" it's out from Porthmeor Beach. I don't see the name in the St Ives info.

Can anyone tell me the meaning of the name (I've forgotten). Despite warnings many bathers swam out to the rock and got into difficulties. Thanks for the site.I hope older St Ives-ites will send in a few stories. Janet

My answer

There

is a rock called Gowna off St Ives that is very dangerous at certain

states of the tide when currents cause the water to turn into whirlpools. This

is known as a tidal race and when young we would never have attempted to swim or

row against this, giving the area a wide berth

Not only was this skill called for on home ground, where the long shore-man was king, but also when they sailed to the unfamiliar waters around Ireland and Scotland and the North Sea fishery. Elders were valued for the knowledge they possessed and could pass on. Rarely was this ever conveyed in written form or identified on charts. Consequently these’ word of mouth’ instructions were heard and repeated many times in a kind of Chinese whisper, the names consequently metamorphosing differently in diverse language areas.

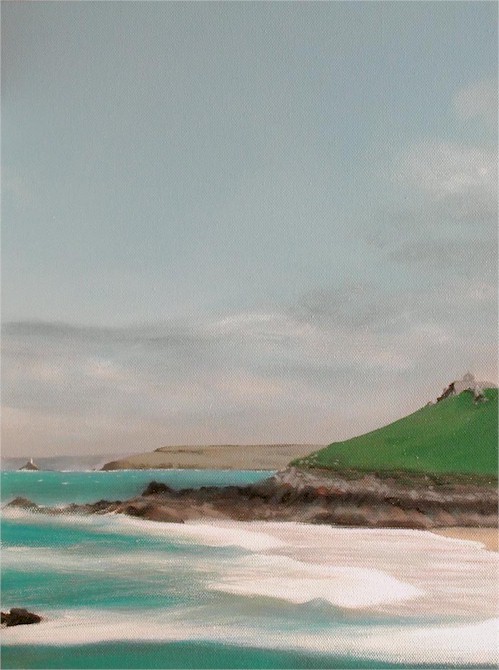

"Gowna and Beyond" Lesley Ninnes

See

more of her work at

Porthmeor Beach is a very dangerous place in an onshore north wind. The St Ives lifeboat Caroline Parsons was lost on the rocks of the island in Jan of 1938 and several other ships have come to grief here. One once was a sailing ship that the villagers managed to reach with a line . the Captains wife and child were on board and the men wanted her to let one of them rescue the child whilst they carried her ashore. She refused to be parted from the child and when they were pulling her through the water the strength of the waves pulled the child from her arms. She was rescued but the child was lost and in grief she grabbed a lantern and ran off across the sand to the rocks, searching . Soon she was once again caught in the grip of the ocean and the light went out. Her body was later washed up under Clodgy Point.

It is said on dark nights that a wandering light is seen to travel across the sands to the rocks under the Chapel at the island. Locals say she has returned to search for her lost child that was snatched from her arms by the daughters of the sea.

There are also at least two places called Gowna in Ireland. The modern Irish word for Gowna comes from the Gaelic Ghabh + naighe = cow + little

Near Glenpatrick there is a series of lochs or lakes high up in the hills. Near one is spot called Sidj Ghabh-naighe = Gowna's fairy mound [or Calf's fairy mound]

Coming back to Cornwall the ancient language was based on the Brythonic rather than the Gaelic so at Sennen Cove there is a large reef called Cowloe and just off this are two rocks called Little Bo and Bo Cowloe. These are thought to have been named for the Cow and Calf appearance of the rocks at certain states of the tide. A cow house in Cornish is a BOWJY. Bow + Chy = Cow + House.

It is possible that the Cornish name for the rock was also 'translated' into English and the elements of both languages are containes in the hybrid name and rememberd as "BO COWLOE" at Sennen but remains more Gaelic as "GOWNA" in St Ives, this place being closely connected, sea trade wise, with the Irish ports. To be aware of these submerged rock hazards was vital to all shipping as they obstructed the entrance to the landing places.

Another name, which more closely resembles Morgana and was given to these half submerged rocks was a MORGOW = Sea Cow. Legend says that mermaids were mythical sea creatures whose siren song lured men and ships to destruction. Once within the tidal grip there was no room to meneuver and shipwreck was invitable. The sea creatures would then disappear into the rocks, hitherto unseen, and the men were left to their fate. They would be dragged down with the under-tow as their sea-bots filled with water and be dashed to pieces on the rocks, their bodies never found. With a death so full of terror theirs soals were condemned to walk this earth forever.

Perhaps these stories were allegorical object lessons in how to avoid trouble: the more graphic nd dramatic the more believable, certainly the more memorable.

The following narrative was based on a Hungarian Folk Tale. Similar stories are told of women and creatures who lived beneath the water and sometimes came ashore. They abound in most countries with a coastline or a large body of inland water. There are also numerous folk myths about drowned valleys and cities beneath the sea. Sometimes the various strands of the stories get woven together and that is how new legends are born. Morgan le Fay, King Arthur’s half sister, was also known as Fata Morgana and according to legend, she lived in a shining palace beneath the sea. Morgans were supposedly sea fairies who lived in the shallows and in seaside caves. It was considered unwise to walk the shore alone at night lest a predatory Morgan be encountered. They particularly liked young, strong fishermen, pulling them under the waves to live lives of ease in palaces of coral.! The story of the mermaid of Zennor and young Matthew Trewhella comes to mind

By Mary E. Atkinson

Down in the

silent, emerald water the Sea King dwelt, and his lovely daughter.

Grand was the palace under the wave and gay with the troops of mermen brave—

Rich with a wealth of sea-gems rare and decked with all that was bright and

fair;

But richest and brightest and fairest of all were the royal maiden’s bower and

hall,

Whose myriad arches, firm and light, up-sprang from clustering pillars bright

Of rainbow opal, and sapphire blue and ruby and crystal of every hue.

The gardens were

full of strange sea-flowers the brilliant growths of the coral bowers—

Gay floating blossoms and stars on stems and stony palm trees with diadems

Of soft, out streaming, delicate blooms whose living and ever-waving plumes

Would disappear if a sound too rude invaded their peaceful solitude.

And gaily along each winding wall pealed lightsome laughter and merry talk,

Or mermaids’ singing, so sweet and clear that the dolphin, passing, paused to

hear.

‘Twas a joyous life they led, and free these beautiful maidens of the sea

Loomed up, great

giants in girth and height, startling and ghostly, of snowy white.

’Twas down at the roots of the mountains old, among the treasures of iron and

gold—

The mountains around whose frosty peaks the storms were playing their wildest

freaks,

Muttering thunders out of the mists, smiting the crags with their fiery fists,

Till the stony splinters rattled like hail down the mountains’ rugged coat of

mail.

But down in the

goblin hall beneath was chill, and awful, and still as death,

Save that the King, in the grim torchlight, kept one faint Echo awake all night,

Repeating still, in a hollow tone, his spur’s sharp ring on the floor of

stone.

Already his brilliant embassy was riding fast to the distant sea,

Through leagues of forest which stretch between, to ask in marriage the Ocean

Queen.

The Sea King’s laughter was long and loud, and echoed by all the courtier crowd:

“Bid the

antelope leave her covert fair and wheel with the bat in the dusky air;

Or the broad-winged butterfly crawl and creep with the sightless mole in his

burrow deep:

The fairy child of the ocean wave could never live in yon goblin cave.

The very sea-shells die on the strand, the white foam melts on the burning sand;

The flowers of the sea their beauty lose, their delicate forms and vivid hues,

If thrown by storms on the fatal shore, and the fishes die and return no more.

Ye may tell your

King that my child shall go when her native ocean currents flow

From her deep sea-bower to his mountain halls, and the surf is breaking against

his walls:

Then, coming by ship to claim his bride, I swear it, he shall not be denied!”

Back sped the troop from the sounding surge, pursued by winds to the forest’s verge;

But scarce had

they passed from the sandy plain into the shadowy gloom again,

When they met their monarch, who, loath to wait for their slow return to the

palace gate,

Impatient, chafed

at the long delay had striven to hurry the hours away,

And quiet his heart with the restless speed Of a furious ride on his fiery

steed.

When he heard the

message he did not speak but his dark eyes flashed at the scorn, and his cheek

Grew pale with passion. His spurs struck deep: not one could follow his

charger’s leap;

And miles behind he had left them all when he entered alone his silent hall,

Tossed the black locks back from his burning brow and muttered: “But One can

help me now!”

It is not for

Christian tongue to tell by what black art, what charm and spell,

What incantation or wicked rite, or whispered words of infernal might,

This Mountain King of a goblin race conferred with the Evil One face to face.

Enough that no gleam on the mountain’s brow foretold the dawn, when a

ponderous plough—

Which was driven by one whose dreadful look not the boldest of mortal men could

brook,

And drawn by shadowy, shapeless forms huge as the clouds in thunder-storms—

A furrow had

hollowed, deep and straight, down to the sea from the palace-gate.

The waterspouts gathered in dread array to meet it there at the dawn of day,

And filled the channel from side to side with a torrent of muddy waters wide.

The waves dashed into the monarch’s hall and flung their foam on the porphyry

wall;

Then down at the feet of those columns old lay silent and motionless, calm and cold.

The goblins were watching the wondrous sight with curious eyes from the craggy

height:

Distorted kobolds

and weirdest gnomes peered out from among the old grey stones,

And there pealed an elfish laugh around, when, sudden as lightning, without a

sound,

A stately galley appeared on the tide, like a sea-gull pausing with wings spread

wide.

The first on board

was the King himself, and after him followed many an elf,

In silk, and velvet, and cloth of gold, and jewels, and splendours manifold.

Down stream they dropped, in the early day, so fast that ere noon the vessel lay

Afloat on the surge of the swelling sea, with flags unfurled to the salt breeze free.

I will not sadden

my verse with all the sorrow which darkened the Sea King’s hall

When the galley appeared on the heaving tide, and the Mountain Monarch claimed

his bride.

As the words were

spoken which sealed her doom, all things seemed altered from light to gloom;

The King was dumb with his sudden grief, and his strong hand shook like an aspen

leaf;

The mermen gazed, in their wild surprise, at the strange intruders, with angry

eyes;

And the mermaids,

thronging with anxious ears, were bursting out into sobs and tears;

But queen-like and still stood the lady there, with the pallor of grief on her

cheek so fair:

Her sea-blue eyes had a sorrowful look, and she calmly spoke, though her sweet

voice shook.

“My father,”

she said, “since your word was passed, though you meant not this, it hath

bound us fast.

We may not dally with vain regret, but guard your honour unsullied yet.

Though my heart clings here, yet I proudly say, my father hath spoken, and I

obey!’

And look! how

broad is the glittering road which leads from home to the King’s abode!

I shall greet you there, in the mountain hall, and often and often shall see you

all!”

It is noon again

on the shining sea, which glitters with pomp and pageantry,

With the dazzling trains of the Elfin King, and a thousand banners fluttering.

The parting is over, the farewells said, and the goblin-galley turns its head

To glide up the watery road which lies like a burnished snake ‘neath the sunny

skies.

The lady stands in

the gilded stern, and nothing her beautiful eyes can turn

From their lingering, mournful gaze toward home, and the long green surges which

break in foam.

But see! how the river’s shores unite! The wondering gazers doubt their sight;

But it is so! The cleft earth shuts again: The sandy beach and the broad

green plain

Close up behind as the ship speeds on, and the lady’s last sweet hope is gone.

She only utters one faint, low cry, one startled moan, but her eyes are dry.

This woe is too

deep for words or tears; despair hath frozen her hopes and fears:

The smile and the sweet, arch look give place to a marble calm on her fair, pale

face.

When the Goblin

King and his silent bride at the palace gate leave the vessel’s side,

It is gone like a bubble, and naught is seen behind them but forests of sombre

green:

The broad doors ope in the mountain wall, and they enter the monarch’s gloomy

hall.

The lady hath dreamed that the crags command a glimpse of the ocean beyond the land;

She has painfully

climbed the mountain height, and eagerly strains her anxious sight;

She scans the wood to its utmost bound, and the far horizon round and round;

But nowhere breaks on her longing view the gleaming line of the ocean blue.

She looks till the watching powers of air take pity at sight of her dumb

despair;

And lo! o’er the forest’s immense expanse the surges play and the bright

waves dance;

The grand blue distant curve is seen, and under the sun the silver sheen;

And nearer, the

surf and its tossing spray, and the white foam blown by the winds away,

The passionate dash o’er the rock-ledge brown, and the white-winged sea-bird

flashing down.

Gazing, she sits

in the dying light 'till slowly the vision has faded from sight,

And only the forest and mountains are there as she dreamily climbs down the

rocky stair;

But only to mount it from time to time, to feast her eyes on the scene sublime,

And live in a dream of a life foregone, and wake and weep when the night draws

on,

And the vision

dies, and the grey rocks cold enclose her within their dreary fold.

Alas, when the Present and Future are dead, and the heart has only its Past

instead,

Mirages the only joys to crave, its life is death and its home a grave!

And now, though

the goblins have passed away [Or never were, as the sages say],

The traveller far on the mountain height may sometimes gaze on the wondrous

sight

Of widespread ocean and distant shore, where only the forest was seen before;

And the peasants sigh, as they view the scene, o’er the mournful fate of the Ocean Queen.

Source: Lippincott’s Magazine Annual 1868, Volume II